This post was inspired by the paper “FairSwap: How to fairly exchange digital goods” by Dziembowski et. al. (1).

Many blockchain protocols suffer from an inherent non-attributable fault. Meaning a fault where the blame can not be attributed correctly.

For example if I want to buy a piece of data from a merchant, everyone else (outside of the transacting parties) can not distinguish between two failure cases:

- The merchant did not send the data

- I received the data but claimed that I didn’t

These issues can be solved by a mutually trusted intermediary that acts as an escrow service in order to facilitate the exchange.

We can also construct a protocol that solves these faults in specific cases using smart contracts.

Example construction

Suppose we have two players A and B.

A has some data data that they want to sell to B.

B only knows the hash = h(data) of the data (e.g. because the hash was notarized by a trusted authority). In this example we proof the claim that the data hashes to hash. We will see later that other claims about the data can be verified as well.

-

In the first step

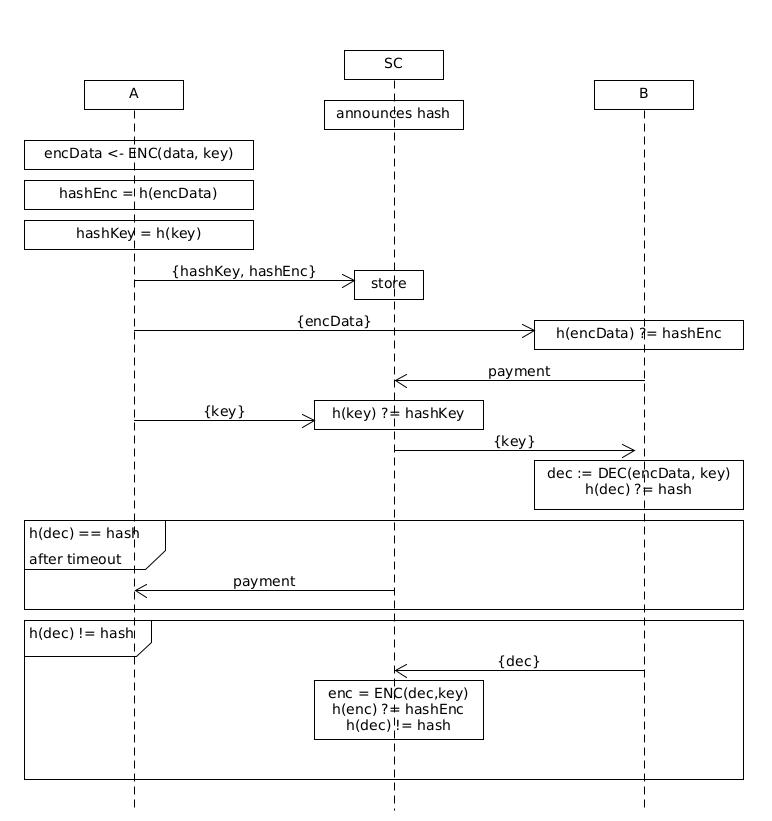

Aencryptsdatawith keykey:encData <- ENC(data, key)and computes the hash of the encrypted data:hashEnc = h(encData)and the hash of the key:hashKey = h(key)NowAsends{hash, hashEnc, hashKey}to a smart contract and the encrypted dataencDatatoB. Bverifies thathashEncmatches the encrypted data they received.hashEnc' = h(encData'); if hashEnc' != hashEnc : abortBsends a conditional payment to the smart contract with the following conditions:- If

Afails to send keykthat matcheshashKeywithin a time period, the payment is reverted - If

Bprovides a valid fault proof within a time period, the payment is reverted - Otherwise the payment is executed and send to

A

- If

-

Asends the keykey'to the smart contract. The contract verifies thath(key')matcheshashKey. Bnow takes the keykeyand decrypts the data they received:data' = DEC(encData, key)If the hash of the decrypted data matches the knownhash, B terminates and the payment is executed. If the hash does not match,Bsendsdata'as a fault proof to the smart contract. The smart contract verifies the fault proof and reverts the payment if the fault proof was correct.- It computes

encData'= ENC(data’, key)` - and verifies that

h(encData') == hashEncandh(data') !=h(data)`

- It computes

- If the smart contract did not receive a fault proof within a certain timeout, the transaction is executed and the funds are unlocked for

A.

Extensions

This example construction is simplified. In practice data can be quite large and publishing it on the blockchain in the case of a fault would be expensive. Thus the scheme can be easily extended to use merkle trees to keep the fault proof size low.

Non-Attributable Faults in MEV

There is an inherent non-attributable fault in the MEV supply chain. Block producers pay validators to include their block. But validators have to take the word of block producers, that the block is correctly constructed and matches the blinded header that they receive first. This fault gave rise to a trusted intermediary, the relay, which connects validators and block producers and verifies that the blocks are created correctly (simplified, they also act as block producers themselves, bundling transactions from searchers).

Construction

In the following construction, we shorten the validator to V and the block producer to B.

Right now the bidding process is kinda backwards in my opinion. Instead of validators buying blocks, they sell block space. But we can easily redefine it. This has some implications on how blocks are constructed, because any MEV now needs to go to the validator instead of the block producer, but they pay for it.

0.1 V solicits bids by announcing that they are eligible to create the next block.

0.2 Block producers bid on the slot by announcing to V that they have a block with hash hash that pays the coinbase value ether in extracted MEV. They are willing to sell the block to V for cost ether. Thus value - cost is the profit for V, cost ist the profit for B. V chooses the block n that maximizes their value - cost.

Vwants to buy block with hashhashfromBand notifiesBof its intentionBsends{hashEnc, hashKey, encData}toVVsigns a transactiontxthat will sendcosteth toBiff- The preimage to

hashKeywas revealed within timeout - No fault proof was provided within timeout

Vsends the transaction{tx}toB

- The preimage to

Bverifiestxand sends{key}toVVdecrypts blockn, signs it and sends it to the networkBsendstxto the network

Fault Proof Construction I

The fault proof works as follows:

B sends the following data {txs, postState, difference} to A.

The fault proof contains {preState, txs, postState, difference}

All transactions are simulated in the smart contract. The smart contract verifies a proof to account of A in the pre-state and the post-state.

The fault proof is valid, if the difference between pre and post-state are unequal to the difference claimed by B.

Problems:

Simulating all transactions of a block within a smart contract is extremely costly and won’t work for big transaction bundles.

Improvements:

- Provide only the preStateHash and proofs to the preState.

- Provide only the postStateHash and proofs to the postState.

- Provide intermediate differences, so only one transaction needs to be simulated

Fault Proof Construction II

The fault proof contains {preStateHash, tx, postStateHash, difference}`.

In this construction we only provide proofs to the preState, postState and one transaction.

B needs to send the following data to V: {preStateHash, tx_1, postStateHash_1, difference_1, ..., sumDifference}.

The fault proofs now has two parts:

- if

Bclaimed thatsumDifferenceis higher/lower thansum(difference_x):Vprovides merkle proofs for{difference_1, ..., sumDifference}to the contract - if

Bclaimed a wrong state transition of transaction with index i:Vprovides merkle proofs for{postStateHash_i-1, tx_i, postStateHash_i}to the contract.

Problems:

Simulating a big transaction is already costly and might cost more than a full block itself.

Conclusion

I think the only viable solution to proving transaction execution on chain is to merklelize the full transaction execution. So that every single operation is part of the proof only the state transition where B cheated has to be put on chain in order to proof the fault.

I’m pretty sure that is exactly how fraud proofs for optimistic rollups work, so these schemes can probably be adapted to work with this.

The only big open problem I see is that the transaction tx might not be valid at point 6 anymore, ideally it should be published beforehand. This would mean that the proposer would need to lock enough funds before his slot to pay out a (theoretically) unlimited bounty.

Even if we can not solve the trustless data exchange in the case of MEV with this protocol, its still a neat technique that can be used to fairly exchange digital assets and thus should be part of the toolbox of every developer.

(1) FairSwap: How to fairly exchange digital goods: https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/740.pdf