I recently stumbled upon the HyperLogLog (HLL) algorithm, which is used to approximate the cardinality of a set. Afterwards I went to sleep and dreamt about using HLL to construct a bloom filter. The following day I had to implement my idea of a HLL-Bloom filter. This post will discuss the HyperLogLog algorithm, Bloom filters and my ultimately futile attempt to combine the two.

HyperLogLog

The HyperLogLog (HLL) algorithm is used to approximate the number of distinct elements in a set.

It consists of three operations: add count and merge. The merge and count operations are not really applicable to our use case, so we will not discuss them in depth.

The HyperLogLog element stores a set of n buckets. Each bucket contains an 8-bit counter.

Add

The add operation adds a new element x to the set.

The element is hashed with a hashing algorithm h = hash(x).

We compute a bucket index i based on the first log(n) bytes of h.

Now we compute the number of trailing zeros of trailingZeros = ctz(h).

If the counter in the bucket is less than trailingZeros, we set the counter to trailingZeros: buckets[i] = max(buckets[i], trailingZeros).

Since we use a hash function with 256-bit output, an 8-bit counter is sufficient per bucket.

Count

The count operation approximates the number of distinct elements that have been added to the HLL.

For this we compute the harmonic mean of all buckets: count = harmonic_mean(buckets).

Merge

The merge operation can be used to merge two (or more) HLLs together. The combined HLL approximates the number of distinct items in both sets.

Each bucket of the resulting HLL contains the maximum of the buckets with the same index in the input HLLs: buckets[i] = max(buckets_a[i], buckets_b[i]).

Bloom Filters

Bloom filters are a very interesting data structure that allows very quickly to allow us to verify if an element was not in a set. It does not allow us to verify if it was in a set though. The basic idea behind a bloom filter is that you have a bitset of a certain size. If you want to add an element you apply a number of hash functions to it and set the bits in the bitset according to the outputs. Now if you want to see if an element was included in the set, you need to hash it with the same hash functions and check if the bits in the bitset are set. If not all bits are set, you know that the element was not in the set. If all bits are set, you know that the element might or might not have been in the set (due to hash collisions).

We use bloom filters in geth for example for the offline pruner. In the offline pruner we allocate a 2GB bitset and insert ~700.000.000 elements (the current state). Afterwards we can go through all stored trie nodes and check the bloom filter if they were included. If they are not included, we can delete them since they are not part of the current state anymore. This allows us to get rid of old state without having to look them up in the original 700 million data set.

Building a Filter based on HLL

In order to build a filter based on HLL, we need to define a fourth function has on the HLL.

Has returns false if the data was definitely not in the data set. It returns true if the data might or might not be in the dataset.

We hash the element, compute the bucket index and the trailing zeros as described in add.

Now we return true if trailingZeros < buckets[i], otherwise we return false.

We can quickly see that if has returns false, the data was definitely not in the set.

Evaluation

We can quite intuitively deduce that the error of the HLL based scheme is quite large. This is mainly because the CountTrailingZeros(CTZ) operation reduces the entropy of the data quite significantly. If we only have one bucket, we would reduce the entropy from 32 bytes (output of the hash function) to 1 byte (log2(256 bit)). The more buckets we have, the less we reduce the entropy, since the index for the bucket is chosen by the most significant log(bucket) bits.

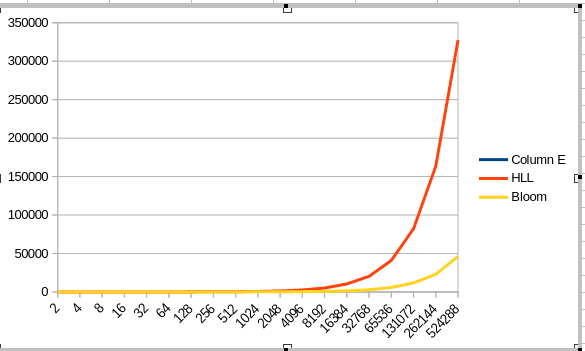

The following graphic shows the number of false positives when inserting ‘2^x+1 elements into a filter of size 2^x`.

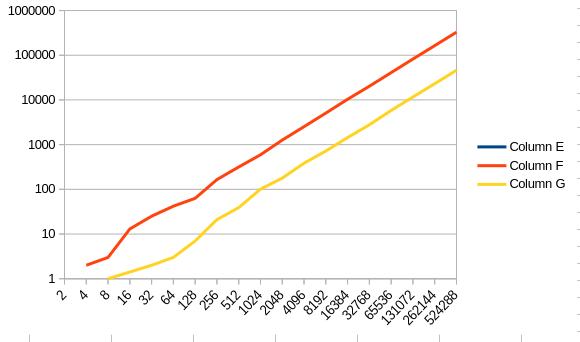

Interestingly, when we chart the error on a logarithmic axis, the following relationship shows.

Thus we can deduce that while the error is significantly bigger with HLL than with the Bloom filter, the rate of growth does not accelerate with the size of the filter as long as the number of elements grows accordingly.

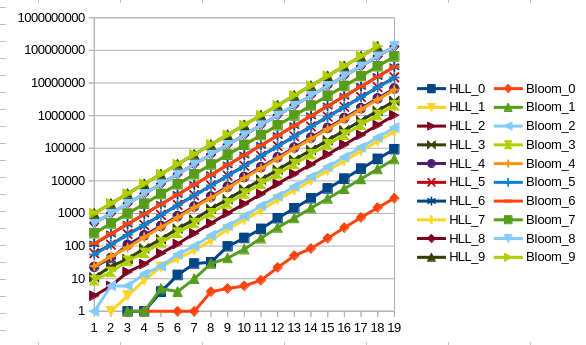

The next question that arises is whether how the error behaves with fuller filters. For this we rerun the experiment with filters of size 2^x and start inserting 2^(x+i) elements with i = (0, 10].

We can see that the difference between the error rates between the Bloom and HLL filter decreases significantly the more elements are inserted. After 2^(x+7) elements inserted into a filter of size 2^x, the HLL filter starts to have a lower error rate than the Bloom filter. These are very contrived examples though, since the idea is to size the bloom filter s.th. the error rate stays very low. At the point of reversal, the error rate for the HLL filter is at 96.35% while the bloom filter shows an error rate of 96.75%. As a reference, the size of the bloom filter we use in go-ethereum’s state pruner is chosen to have an error rate of 0.03%.

Benchmarks

Now that we established that the HLL filter is significantly worse than the Bloom filter, we should take a quick look at performance to find at least one redeeming feature of the HLL filter. The following benchmarks try to insert elements into filters of size 2048. The bloom filter uses 4 hash functions. We can conclude that the HLL filter is twice as quick as the Bloom filter.

BenchmarkHll-8 17189948 69.25 ns/op 64 B/op 2 allocs/op

BenchmarkBloom-8 8753673 135.8 ns/op 64 B/op 2 allocs/op

Conclusion

In conclusion we can say that the HLL filter looses significantly on efficiency against the Bloom filter. While it is twice as fast as the Bloom filter, the results are significantly worse. Only in a case where significantly more elements than slots in the filter are added, the HLL filter has a slight edge, since it is very hard to fill up all buckets to the top.

All in all this was a useless experiment, but a fun one at that.

The only real bright spot is that this experiment resulted in a very simple HyperLogLog library in golang, which can be found here: https://github.com/MariusVanDerWijden/go-hll. Its not production ready yet, but it can be used to quickly understand the HyperLogLog algorithm.